2 Problem Statement, Objectives and Criteria

Here we talk about our understanding of the problem (both in a general sense and more specifically in our research goals), and the questions for each objective that brought us to choose the criteria.

2.1 Theoretical framework: The idea of Ecological Restoration

Our group’s understanding of ecological restoration is reflected well in the evolution of debates and the resulting definition of the discipline, developed by the newly formed Society for Ecological Restoration (SER) in the 1980s and first published in 1990.

Ecological Restoration is the process of intentionally altering a site to establish a defined, indigenous, historic ecosystem. The goal of this process is to emulate the structure, function, diversity and dynamics of the specified ecosystem. (Higgs, 1994)

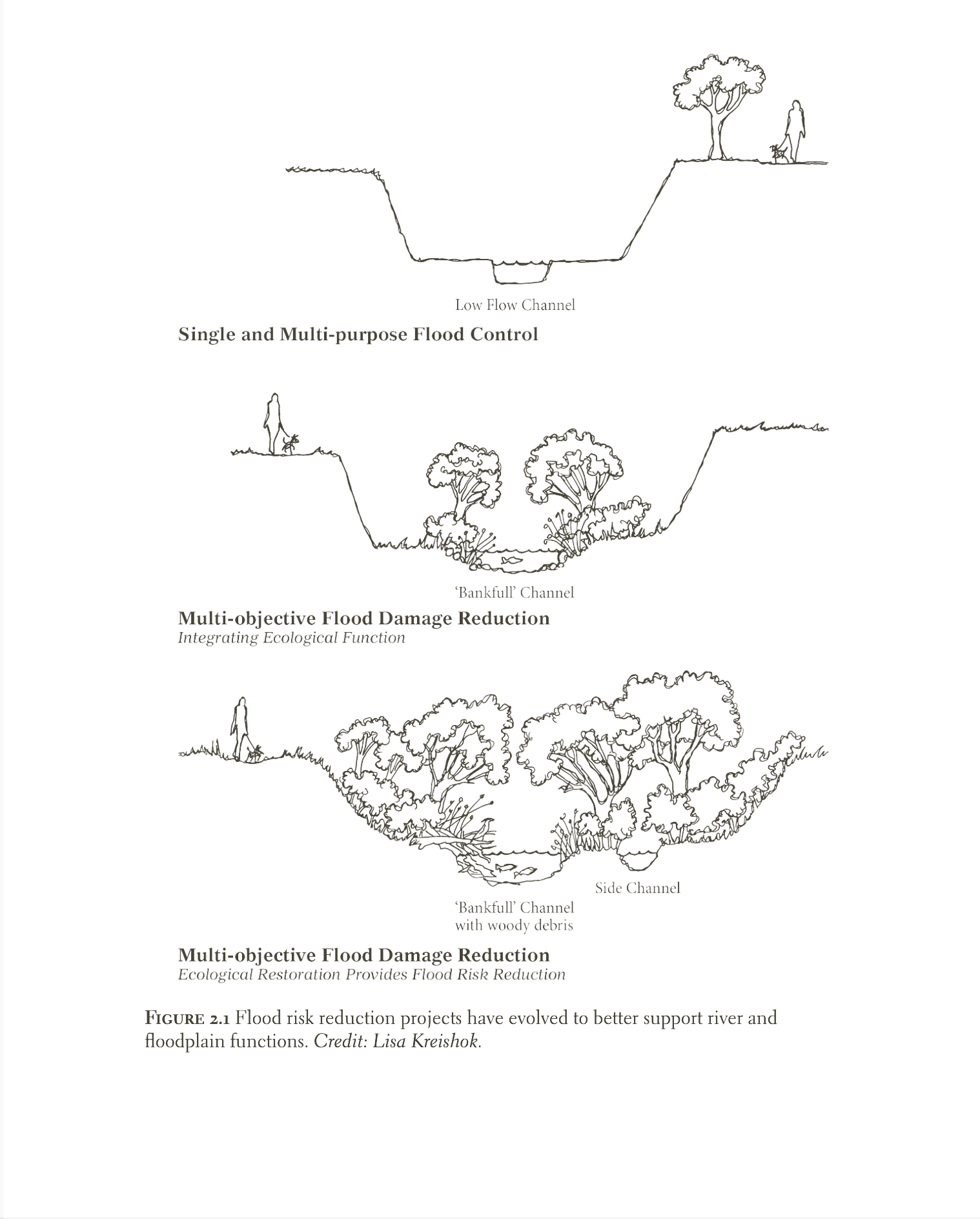

What to leave behind —The emerging movement sought to move beyond human-centric notions that had shaped the goals and perspectives of restoration efforts. It aimed to reposition humans as part of complex ecosystems rather than the central focus of resource management. Terms like ‘conservation’ and ‘preservation’ were avoided, as they implied managing “natural resources” for human use or protecting wilderness for its scenic value. At the heart of earlier approaches was the objectification of nature as a resource to be used, enjoyed, and controlled: projects often sought to simplify streams and floodplains, eliminating ecological dynamics seen as barriers to flood control and land development. By the late 1990s, it was increasingly recognized that flood damage reduction and ecosystem protection could be achieved through the same project. This marked a shift in thinking among floodplain managers—from single-purpose flood control to integrated river and floodplain interventions that mitigate flood impacts while providing ecological benefits.

Even the aforementioned definition of restoration sparked debates about how to define “indigenous” or “historic” ecosystems, given that ecological systems constantly evolve. This raises the question: which point in history should we aim to restore to? After all, there is a difference between restoring for maximum biodiversity and supporting the local dynamics of a functioning ecosystem. Especially in urban contexts, practitioners recognized that land use disturbances made it unrealistic to recreate indigenous or historic environments as they once were. This is why the new approaches to restorations were influenced by the imperative, already emerged in the 1930s, of repairing or reversing damage caused by human activity on ecosystems.

What makes an ecosystem and its restoration — What persists of these definitions are the core variables that should inform any restoration. First, the structure of forms composing an ecosystem — the spatial pattern or arrangement of landscape elements (patches, corridors, and matrices) which strongly controls movements, flows, and changes (Dramstad, Olson, and Forman 1996). Second, the ‘ecosystem functions’, later redefined as ‘ecological processes’, intended as the “dynamic attributes of ecosystems, including interactions among organisms and interactions between organisms and their environments” or more simply put by Dramstad, Olson, and Forman (1996), the movements and flows of animals, plants, water, wind, materials, and energy through the structure. Lastly, a restoration project should aim to provide resiliency, the ability of the ecosystem to sustain itself without regular maintenance or interventions: the native plants and animal species should thrive, sustain reproducing populations necessary for their stability, and be capable of enduring periodic environmental stress events (such as a fire or flood) that serve to maintain the integrity of the ecosystem.

Finally, a suggestive and far-reaching paradigm was provided by one of the founders of the movement, William Jordan, who argued that individuals and communities must be active participants in ecological recovery, and that healing natural systems would also foster the recovery of human communities. The benefits would go beyond an economic view of the use and enjoyment of our collective natural resources, encompassing the re-creation of a “sense of community” and a “sense of place.” Restoration should aim to create functioning environments where diverse species can thrive while also restoring social and historical identity in a generation increasingly disconnected from place by freeways, strip malls, and car-centric development.

2.2 Problem Statement and Research Question

Along with the Elbe river, Dresden comprises a dense network of streams, which are spread out across its fabric. Presently, the streams are secluded from being a valuable part of the city. The problems are characterised by ecological issues, inappropriate land use by residents, and artificial channelling (Project case description). They, along with the Elbe river hold potential to become elements of integrating the ecological and social functions of the city by reclaiming the historical identity of waterfronts and restoring natural habitats. Therefore, there arises a need to understand how to integrate these streams into the network of protected green areas and public spaces, while maximising their contribution to biodiversity while adapting to the risk of flooding within and around the city.

These concerns and identified potentials beg the question that, how can urban streams be restored and integrated in Dresden’s fabric, such that there is a synergy between human activities and the natural environment?

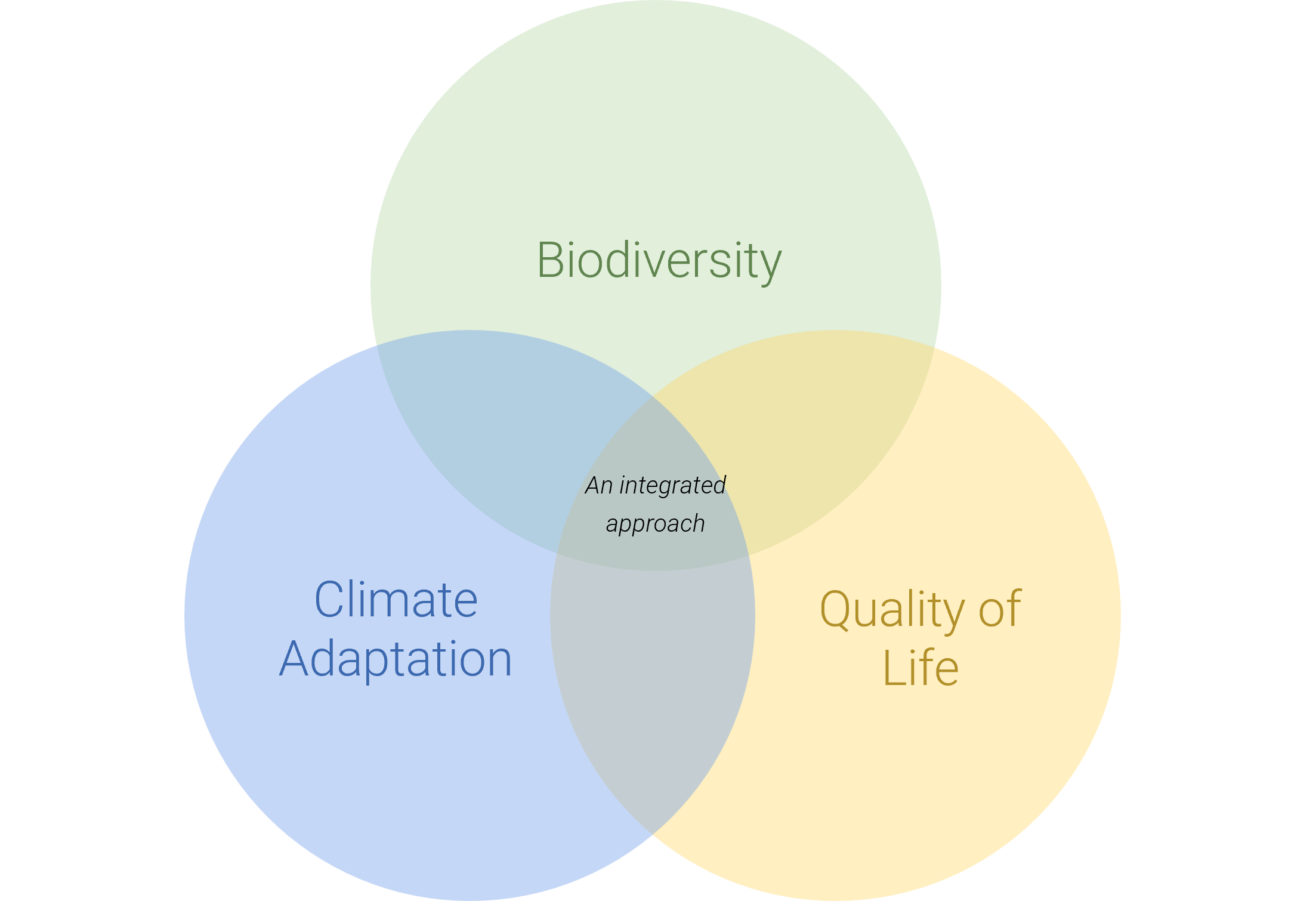

To articulate the challenges and identify the potentials to answer the question, the analysis is divided into three sub-research categories under the broad themes of biodiversity, climate adaptation and quality of life. Each theme has specific criteria with its attributes, which are analysed, measured and weighted against each other to arrive at the final decisions.

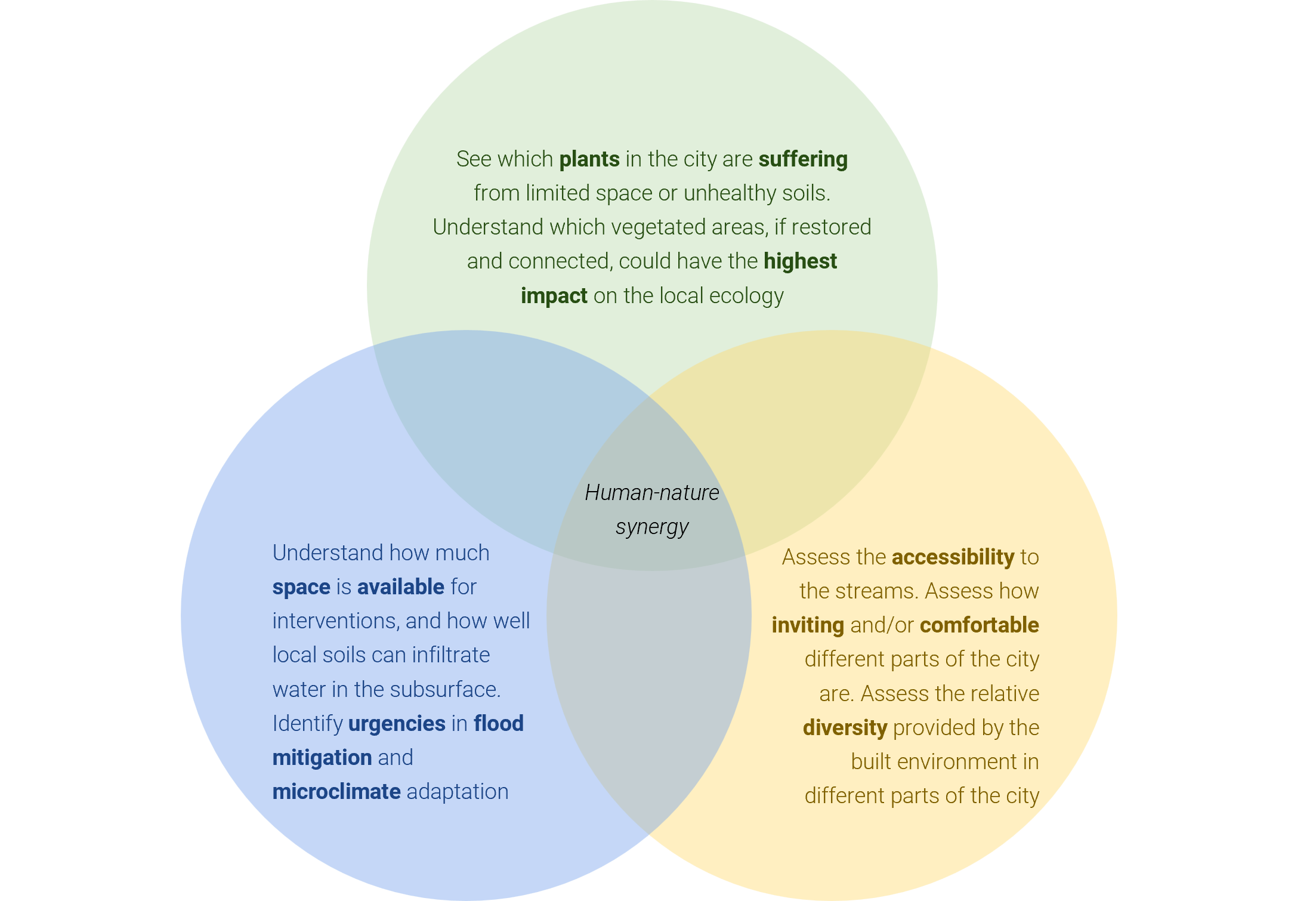

2.3 Biodiversity: What are the potentials and current urgencies in the integration of the natural elements in the urban landscape of Dresden?

The criteria of connectivity and environmental quality are chosen to improve the existing habitats and further expand them.

- Connectivity — The attributes defined within connectivity aims to identify the potential of improving the connections between the existing vegetation areas. The potential green corridors along the streams are highlighted by using the ‘greenspace’ layer from OpenStreetMaps. The layer consists of the various typologies of green infrastructure of Dresden’s fabric. These are a combination of planned and recreational spaces (parks and traffic-side greenery) and natural spaces (forests, meadows, grass). To identify the potential near the streams, the following sub-criteria is defined for measurement:

- Green-Blue connectivity: Blue-green infrastructure (BGI), combining semi-natural and engineered elements, offers multifaceted benefits like stormwater management, water purification, heat mitigation, and habitat provision (Perrelet et al. 2024). To analyse the gaps in vegetation along the stream corridors, the greenspace layer from OpenStreetMap is modified to see the fragments between vegetation which lie within a 250 meter buffer from the streams.

- Environmental Quality — The attributes defined under quality aim to assess the quality of the ecological environment near the streams. This is done by analysing the soil quality using the Bodenqualität (soil quality) layer from the Dresden open data portal and by analysing the plant health using the Sentinel-2 data from Google Earth Engine.

- Soil quality: Soil quality indicates the capacity of the soil to support ecological functions. Within the objective of integrating natural elements in the landscape of Dresden, it becomes crucial to understand where the areas with poor soil quality lie so that they can be restrored for vegetation.

- Plant health: Plant health reveals the existing plantation which is in poor quality, and is hence also impacting the health of the overall ecosystem.

2.4 Climate Adaptation: What are the main challenges and the potential spatial interventions to adapt to climate change?

To address this question, we focused on identifying both the areas most vulnerable to climate-related hazards and those with potential for ecological intervention.

Flood safety - Flood safety was assessed using hazard data provided by official Saxon authorities. These datasets simulate the spatial extent of flood events expected to occur once every 20 years (HQ20), 100 years (HQ100), and under an additional extreme scenario. Although often referred to as “flood risk” data, these layers are more accurately understood as hazard maps, as they depict the probability and extent of water presence without accounting for exposure or vulnerability components that would complete a full risk framework.

This distinction is important because it highlights both the potential and limitations of the data. While useful for planning, these layers do not incorporate social or infrastructural vulnerability, nor economic or insurance considerations. As Rözer et al. (2020) note in their analysis of Germany’s flood risk governance, despite a gradual shift toward anticipatory systems, there remains a lack of strategic focus on how to achieve resilience, and underinsurance remains widespread. Our use of this data acknowledges these limitations while offering a practical tool for relative spatial appraisal.

Soil infiltration - The infiltration capacity of the soil was used as a proxy for local water absorption and groundwater recharge potential. The data were sourced from the Saxon State Office for Environment, Agriculture and Geology (LfULG) through their Web Feature Service and derive from a layer titled “Wasserspeichervermögen des Bodens”, or water storage capacity of soils.

This attribute represents the estimated ability of the soil to retain water during precipitation events, which is critical for understanding flood risk mitigation, drought resilience, and ecosystem health. While not directly a risk indicator, infiltration capacity contributes to the regulating functions of the soil and informs where permeability may reduce surface runoff and enhance local hydrological balance.

The classification includes five categories ranging from very low to very high infiltration capacity, allowing us to incorporate this into a relative index across urban areas.

2.5 Quality of Life: How accessible, inviting, and diverse is Dresden’s public space, and how can it reach its full potential?

Urban stream restoration is increasingly used as a strategy for improving the physical and ecological conditions of degraded urban streams. Beyond ecological benefit, it also has a social impact for enhancing the quality of life for the residents living in urban areas. Urban stream restoration can provide amenities, recreational opportunities, and environmental health benefits that contribute directly to residents’ well-being. Therefore, it is important to foster awareness and supportive attitudes toward stream restoration projects, while also addressing the issue of just distribution and equal access to streams. Below are the three key aspects of restoration projects support this benefit:

- Attractiveness — Aims to assess how inviting Dresden’s stream corridors are as public spaces. It involves evaluating the visibility, how the city is visible from the streams and Elbe River’s corridor. This analysis was conducted using a viewshed analysis based on example points along Dresden’s waterways, combined with a DSM file which contains elevation information and physical obstructions such as building and trees. By identifying areas with good views of the stream corridor, future interventions can make these areas more appealing and strengthen their role to provide amenities and public spaces for people in Dresden.

- Peripherality — Aims to analyse how accessible Dresden’s streams are to the public, especially within walking distance. This is done using accessibility analysis combined with population data to show how well-connected the streams are to the area where most residents live. We call it peripherality as we reversed it for our MCDA analysis (as we want higher accessibility to have lower values).

- Diversity — Aims to evaluate the diversity of land uses around the streams to support multifunctionality and encourage varied public use along the stream corridor. Areas with diverse land use (such as a combination of residential, commercial, and green spaces) tend to attract a broader range of users and encourage inclusive stream environment. In contrast, areas with single or low land-use diversity indicate less inclusive and/or underdeveloped areas that need interventions to unlock their full potential.

The two references we used for this part are Bernhardt and Palmer (2007) and Scoggins et al. (2022).

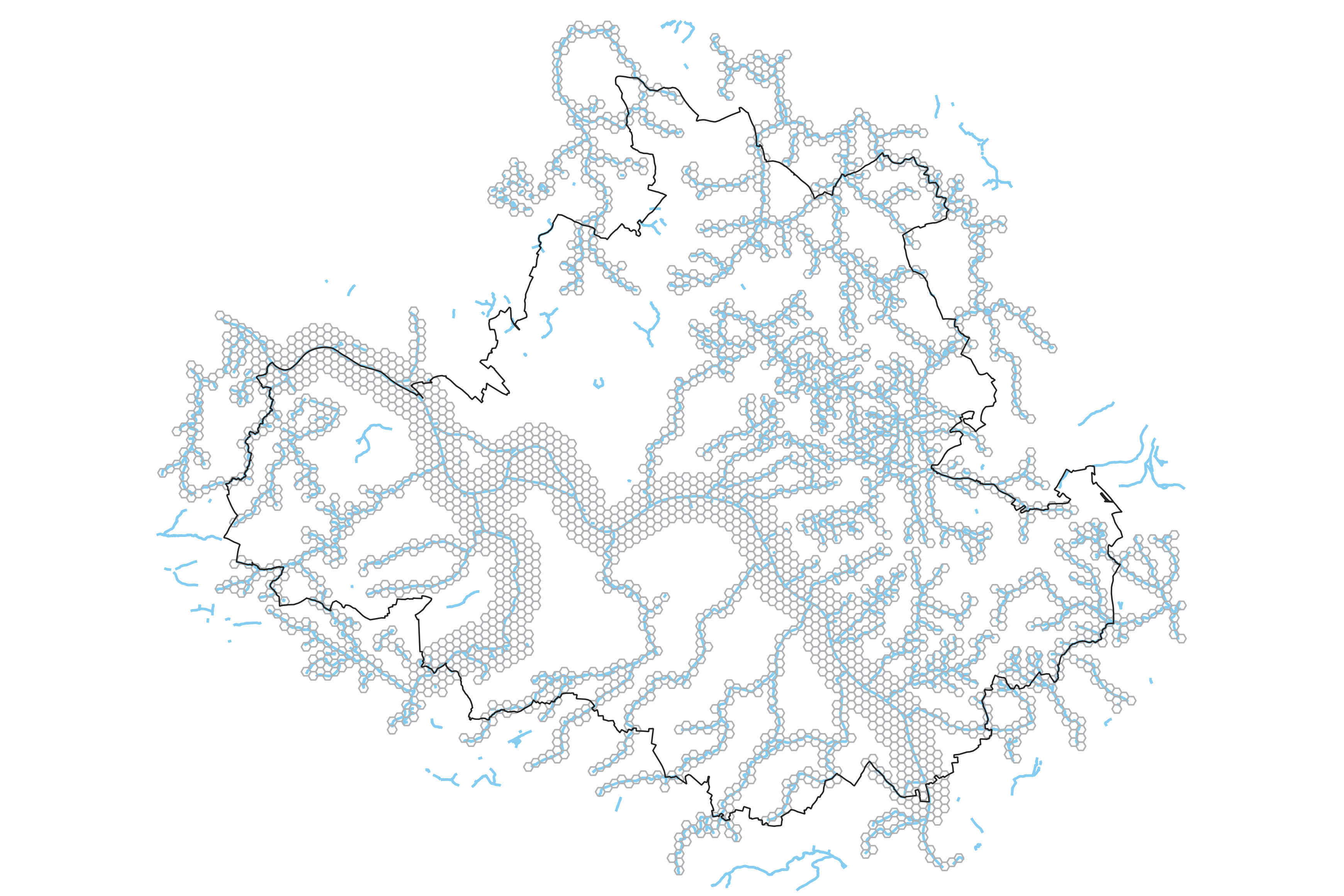

2.6 Spatial Units and other notes

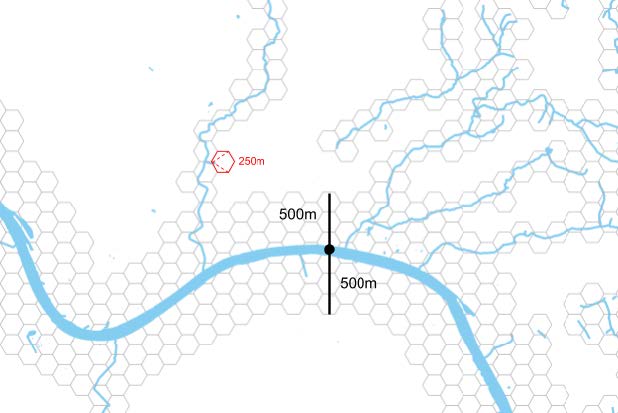

The spatial units used in this study are hexagons with a dimension of 250 meters. The study area of Dresden is divided using a complete surface of a hexagonal pattern. Then it is overlaid with the water stream network and river body from OpenStreetMap to keep only the hexagons that intersect with at least one stream. Finally, the isolated hexagons were removed.

To explain why the Elbe river was included in the study area is that the river is a key element that has shaped the urban growth throughout decades and many spatial and environmental features are affected by this water body. Moreover, the Elbe is spine to most of the streams across the city that branch out form it. The river itself creates a vast network of waterways all across the urban, periphery, and forest areas. Otherwise, only picking the stream network would isolate the southern bank structure from the northern bank streams in which were clustered inside the forest areas which don’t hold the potential for interventions. Therefore, the decision was made to consider the Elbe river and streams as whole water network within Dresden’s boundaries.

The prominent reason behind picking the dimensions of 250 meters is based on two main reasons:

- The walking/biking distance: the estimated radius is used to evaluate the spaces around the water stream within a low walking distance, as pedestrians or cyclists have the highest exposure and engagement with urban streams.

- The space but not the line: the spatial units are also going to determine the probable area of intervention. Then the streams are not the only lines that need to be changed, but the space surrounding them is also affected in both ways. This space includes the buildings, facilities, and natural habitats that all have synergies along with their neighboring stream structure.

The spatial units are also filtered by a 500-meter buffer of the main river, Elbe, as it is one of the key spatial elements that have shaped the city’s form, functions, mobilities, and identity that cannot be overlooked. So, a larger buffer of hexagonal spatial units where divided in the buffer zone of the Elbe river as it covers a larger area of the urban fabric in terms of biodiversity, morphology, climate adaptation, and quality of life.